As described in the first post on California College of the Arts (CCA), the Center for Cultural Innovation (CCI) selected CCA as a CIIN partner because of the college’s interest in developing new types of donors who invest in art and design projects with tangible social, environmental, civic, or community benefits as “returns.” As described in earlier posts, CCA will use CCI’s funding to secure impact donors of activities in three departments: Center for Arts and Public Life (CAPL), Secret Project, and the Interaction Design Department. For this third post, we interviewed the Founding Chair of CCA’s groundbreaking Interaction Design Department, Kristian Simsarian to describe how arts education is shifting to prepare artists for a multi-bottom-line world.

Simsarian is a leader in design, creativity, education, and innovation with over 25 years of industry and academic experience. He has worked at the foremost technology invention labs around the world, and served as a design and business leader at IDEO for over a decade. As founding chair of the California College of the Arts BFA and Masters of Interaction Design programs, he has been highly influential in creating educational experiences that incorporate design thinking and deep craft. In 2014 he co-authored Udacity’s first design MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) with Don Norman, titled “The Design of Everyday Things,” which enrolled over 80,000 students around the world. He received his BS from Columbia University, his MS from the University of Virginia, and his Ph.D. from the Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm.

At the heart of CCA’s Master’s program in Interaction Design (“IxD”) is the Social Lab, a cross-divisional, multidisciplinary hybrid lab space that Simsarian created to guide students in taking their design skills into the world. His underlying motivation in creating the programs at CCA was to “give students a creative path to shaping technology and improving the world” that he wished he had when he was a student, himself:

In the Social Lab, IxD project teams collaborate with community organizations and local partners to identify prevalent social challenges, seeking a systemic and holistic understanding of those challenges and their root causes. The teams then engage community members as partners in the process of designing tools and systems that can fundamentally address those challenges, deepening the strength, resilience, and impact of the neighborhood and its constituents.

We spoke with Simsarian about his experiences in using interaction design to increase human, intellectual, and social capital, from within an academic context:

CCI: Could you describe the theoretical soup that IxD emerged from?

SIMSARIAN: I used to be at IDEO full-time, and at the time I was interested in the intersection of people, culture, technology, and systems; particularly systems at scale. After co-founding and building the Software Experiences digital design business there, we decided that it needed to be part of everything we did at IDEO. So we took it from being a siloed vertical to horizontal, where we had 20 people in our business unit managing projects run by 60-100 designers spread out across the company. It ended up growing fast and becoming a viable, $20M business, but we still had this kind of bugaboo where we couldn’t find talent, or we were just killing ourselves trying to get visas for folks from overseas. It seemed like every time we were looking for pragmatic design talent we had to go to Europe.

When I was just starting to teach at CCA, I had the ear of CCA leadership a couple of times, and I said: “You guys gotta start a program here.” A year later they came back to me to convince me to launch it. It just seemed like the right fit–combining my academic and innovation skills–then we just needed to figure out what it needed to be. It seemed natural to apply the design thinking process to creating a design thinking program. We went deep on co-creating with industry, academics, and parents to apply the design thinking process to founding this new curriculum.

So in 2015–as we were redoing the MFA–we realized there was an opportunity to make it less of a craft-focused program and more of an exploratory program, and that left an opportunity for more pragmatic programs. The first new program was the “MDes” (Masters of Interaction Design) which is a three-semester, one-year graduate program for “craft-shifters”–someone with a background in graphic design, industrial design, architecture, or engineering who is transitioning to a new practice and wants to minimize time in school. It gives folks leadership skills and craft skills, and the curriculum is inherently inclusive: designing for the people that tech isn’t designing for.

CCI: Why was this a relevant or important new field of study to offer?

SIMSARIAN: I have a tendency to try to think 10 or 20 years ahead of the market, whatever I’m doing, so it was critical to me to be industry-leading vs. industry-following. Now, this was pretty polemic at the time, but on top of the opportunity to design a new program, I wanted to explore how we might design more for people and society and not just for the needs of venture capitalists. It just doesn’t seem like tech was taking responsibility. I felt the students were drifting further and further away from human problems, and I felt like we needed a social lab working to discover and meet the needs of real people; to be a counterbalance to the technical fetishism. Societal impact and human needs should be just as present as technical imperatives. The question is how do we actually do that?

Some of that goes back to the ‘90s when I was doing my Ph.D. work in human-robot collaboration in Sweden, which was partly sponsored by Swedish unions! They invested because they were interested in worker self-actualization. They saw the factories becoming robotized, and they didn’t want the coming wave of automation and robots to de-skill their workers. Unfortunately, the unions in the U.S. aren’t on the same mission as in Scandinavia. The laws here don’t enable unions and management to be very cooperative or generative. We have more of a grievance system, which seems counter to innovation.

So…who represents people here in the U.S.A.? How can we have our students grounded in human-centered design and community needs? How can tech function for social good, and do the work not being done by the VC-fueled community? I started to look to community organizations to explore how we could use the real world as our classroom, and benefit the organizations at the same time. This seemed like win-win.

CCI: And how did you translate your mission into structuring the curriculum?

SIMSARIAN: I describe it as developing a spectrum of capability in the students, where they grow from “pair-of-hands” [pure craft-based work], to consultant, to partner, to social entrepreneur. We want students to ask the kind of questions that you can’t ask when you’re just a “pair of hands.” We want them to awaken to their leadership potential and the idea that when you are doing what you want to do–you’re unstoppable. You could probably make a 2×2 to visualize that balance of utilizing skills vs. soul, but it comes down to “How much say do I get in what I am working on?” It’s ultimately about student agency.

As far as the actual curriculum, we say that we’re educating “hands” which is craft, “head” which is process, and “heart,” which is what’s needed and valuable. Our curriculum has two core classes in leadership that we’ve evolved significantly, and that we now call Communication by Design, and Strategy by Design. Those courses are taught by the amazing Sharon Green, who has a Cal Berkeley Ph.D. in organizational psychology. The students work with nonprofits as consultants, which is in contrast to the social lab where we try and work with community partners as partners.

Now, we used to try and run them at the same time, but it just confused the heck out of the students. We used frameworks and diagrams and tried to reinforce that these are different modes of working, but it was tough on the students. They had difficulty distinguishing between clients and partners because to them it was still just a word change as opposed to a mode change. So this year we’re not teaching those classes at the same time at all, and we are making the different working relationships part of the program’s learning objectives.

CCI: How was the experience of finding community partners willing to work with students, and then setting up mutually beneficial structures for that work?

SIMSARIAN: There are a lot of nonprofits that aren’t really “community partners. We started to get into the “13 words for snow” problem. Luckily, we ended up working with partners like the African American Art & Culture Complex (AAACC) which has been the long-standing home of Black arts in the Bay Area. Now that’s an organization that represents a community that’s under disruption in San Francisco and facing all sorts of complex challenges such as gentrification and socio-economic issues. The direct need was just loud and clear and present there, and they were willing–and curious–partners. The complexity makes it a great context for experiential learning.

Another partner that we’ve worked with is Glide Memorial Church. It’s a huge organization known for being an open, inclusive church community, but they also have four or five major social missions going in addition to their ministry; like feeding the homeless, sheltering the homeless, providing direct support services for working poor families, daycare and literacy services for women. It’s big, it’s well-organized, and it’s well-funded, so they were able to plug our students’ concepts in and run with them. Some of our best initiatives have been student-discovered, so now we’re teaching how to create and execute a memorandum of understanding and give the students agency to create their own partnerships.

CCI: And how do you judge the outcomes of your students? What kinds of change do you expect to see if they’re successful?

SIMSARIAN: CCI actually helped fund several of our most successful projects! The first year that we worked with the AAAC they just don’t really have the capacity to work with all of our students, but one project we did end up doing was with Marcus Bookstore. That project is still in progress because there’s been a leadership change, but it looks hopeful to complete.

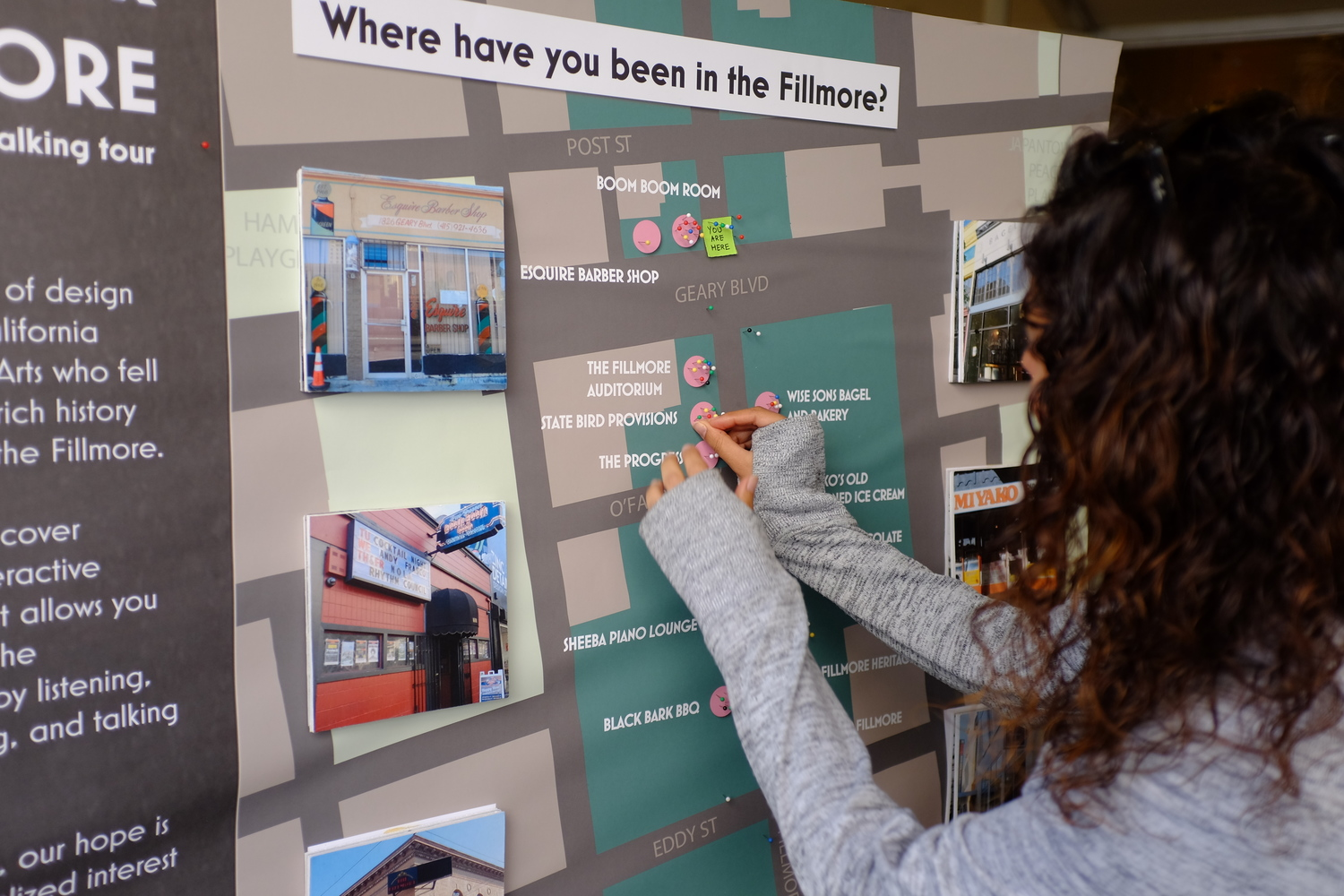

But by working in that neighborhood, another group ended up working with the Fillmore Merchants Association to create a project called Discover Fillmore which is still running. It was an audio tour homage to the neighborhood that featured the disappearing voices of the area. State Bird Provisions [an award-winning local restaurant] actually loved it so much that they paid our students to give all of their 50+ employees the tour. They wanted their employees to feel connected to the neighborhood and not just be part of the gentrifiers.

Project Dahlia was another terrific project, that had a funny beginning. These students were interested in homelessness and sort of had this assumption about “Why isn’t anybody doing anything?” So I said, “Ok, why don’t you go out and investigate that. Go find out if there are actually no organizations working in that space.” So of course they came back the next week and they had found about a hundred organizations without really looking too hard. And the orgs were all over the place: people giving food, people giving shelter, people giving baths, setting up credit structures, changing policy; all sorts of things that were not necessarily money.

What they ended up focusing on was homeless women, which they discovered were underserved. So they found this really particular niche, and they really dug to find out what was needed. CAPL got involved too. And at some point they ended up finding a woman that was starting a nonprofit around women’s issues, and she’d been in the news recently. So they went and worked with her as a partner–they did some pair-of-hands work, like basic design work and got a logo going for her, that sort of thing–but then it turned out that this woman had a whole room full of donated feminine hygiene products that she needed help unloading. So they put their heads together and started to create these really nicely-crafted packages for women’s monthly hygiene. Then they put it into action and developed a pretty amazing operational plan to disperse those materials.

As far as outcomes…I’m very interested in measurement, and we do teach it. I have friends who are in funding, and measurement is everything for them. Funders aren’t investing in projects, they’re investing in outcomes. So if you want to get the second project you better demonstrate outcome. So we always do a baseline assessment and decide what to measure. Now, we’ve never been able to get to a point where we do deep statistics, but we definitely do qualitative measurements. What about social capital, cultural capital, and human capital? How about spiritual, psychological, and knowledge capital? What about those mindsets? This is a framework for students to understand alternative capital and to have it inform their research. So we don’t measure impact in financial return, but alternative capital such as social, human, and knowledge. We use a great framework called MetaCapital, designed by an advisor to the program. We haven’t gotten quite as far as I hope to, yet–and neither has society–but we get students to a stage where this mindset is informing their research, it’s informing the way they ask questions when they prototype, and it’s informing their ultimate assessment of their work.

CCI: Are there particular qualities you look for in successful applicants to the programs?

SIMSARIAN: We’re definitely looking for certain qualities like caring about the world, capacity for empathy, etc. We ask questions like, “What work have you done in your life to prepare you to work with community partners?” or, “What’s a really important, complex social challenge that you want to work on?” We’re ultimately looking for capacity; people that can come in with a raw mindset, that are open to systems bigger than themselves. We actually have to include some Wikipedia links in the application now because there’s so much new language to digest just in the application. This is probably another example of us running ahead of dominant culture.

CCI: And what role do you think design and design-trained students might play in today’s economic and political milieu?

SIMSARIAN: There’s no organization on the planet that doesn’t need a designer who knows how to shape technology. Everybody is being disrupted, enabled, and amplified by technology. Right now the stakes are high. We’re all feeling it. I mean, we’ve got tech companies being challenged on allegations of election tampering! Or let’s look at another threat: what about the increasing social divisions? Designers need to rise to that challenge and technology is going to be part of that. Another one is autonomy: machine learning is going to start to create norms. The current culture is pretty normed around white men – and that’s not going in a good direction. So the question is “What is the new normal?”

So we’re asking students to find themselves in that system; try different hats on; let go of previous constraints. And we’re going to be more fluid: there are all of these new digital platforms where you can seek funding if you have a good idea, but that’s where the power of design is going to come in to play. Anyone can have an idea–but it’s the convening, and the showing, and the envisioning, and the collective work that is the important stuff.

CCI: Where do you think art and design training is headed in the future? What role will–or should–it have in society?

SIMSARIAN: Things need to stay local and the focus needs to remain in the community. It can’t just be a hand-off. It needs to be about relationships and about partnership and it needs to go deeper than a transaction. The social lab is a kind of world cafe-meets-design thinking-meets-system thinking-meets-agility. When you bring those things together you can accomplish really awesome results. Find the social needs–not just the consumer needs–and then figure out what the minimum viable offering is, figure out how to fund it and keep it going and stay attuned to the value, and remember what societal need brought you there in the first place. Of course, to actually accomplish what we’re trying to do at the social lab we can’t keep scraping for meager resources either. Just like any other large-scale challenge, we need 10 or 15 million dollars to start a real Center and do real work at scale.

As far as the students–at CCA we give individual attention and committed faculty, and we get very personal. We have the luxury of saying to our students: find the thing that brings you joy and that you care about so much that if someone tried to take it away, you’d bite them. Now I believe that this model is great, but I’m not sure how to make it economically accessible. So we really need to focus on future skills; the kind of things that integrate and the kind of things that really focus on human capacity. Almost every rote job is going to disappear in the next decade or so, even menial coding jobs. So it’s not problem solving–that’s AI–we need to focus on problem-finding, collaboration, flexibility, and comfort with ambiguity. Because the machines will take care of all of the situations that aren’t ambiguous.

CCI: And why do you think art students, in particular, are the future of “problem-finding”?

SIMSARIAN: You gotta break creativity down. The creative capacity for a growth mindset versus a fixed mindset is so important. We can’t keep doing things the way our “grandpappy’s did ‘em.” Tradition isn’t sufficient any more. The biggest challenge right now is that our technology doesn’t have wisdom. It doesn’t have a sense of what the right thing to do is, so it doesn’t know where it needs to go. That’s what I want to call for: wisdom in technology.

And it’s going to be even more important in an increasingly, and inevitably, diverse society. The “Berkeleys and Stanfords” basically just scoop up all the valedictorians every year, put them in the company of other valedictorians, point them at good material, and it’s all a bit self-driving in terms of education. But try to do that with a more diverse population and things are very different! Vassar won an award recently for [enrolling 17% first-generation college students]–well, CCA is already 33% first-generation! People think art schools are cloisters for rich kids, it ain’t so at CCA.

So what is worthy of being solved? Design is applied art, just as engineering is applied science. We’re going to need creative people in a world where everything that can be compartmentalized is solvable by machines. Anything that is interesting–whatever isn’t going to be solved by machines–is a complex social challenge, and that process can’t be automated easily. That’s where the workers who are inherently creative come in.